At first glance, central Australia’s Red Center might seem vast and empty, a canvas of rust-colored soil, sparse shrubs and endless sky.

Learn to read the landscape, though, and you recognize you’re walking in a living archive that tells a story shaped by ancient fires, waterworks and tens of thousands of years of Indigenous care.

For travelers exploring Uluru and Kata Tjuta, learning to read this landscape reveals something extraordinary: the Outback isn’t barren—it’s elegantly written.

Climate, conservation, and culture converge in Australia’s interior, and learning to interpret the land transforms sightseeing into something deeper and more rewarding.

Here are some ways fire, flood and time shape this storied landscape—and how you can begin to understand it.

The Australian Outback Is Not Empty: Landscape as Living Archive

The myth of the Outback as empty or unused land is a colonial one, born from unfamiliarity with arid ecosystems and a lack of understanding of Aboriginal knowledge systems and management practices.

In reality, Australia’s Red Center holds both biodiversity and meaning. Over 6,000 plant species grow here, along with hundreds of reptiles and birds specially adapted to this climate. What may look like a barren expanse is in fact a mosaic of microhabitats and cultural memory.

To Aboriginal Australians, land is not just landscape; it is Country, a concept that includes people, plants, animals, water, and story as one interconnected whole. Nowhere is this more evident than around Uluru-Kata Tjuta, where Tjukurpa, the Anangu law and cosmology, binds the past, present, and future.

Tjukurpa explains why a rock leans a certain way, why a spring flows from a particular spot, and how people should live in relation to them.

Recognized by UNESCO for both its geological and cultural significance, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park is more than a destination—it is a sacred text written in stone, song, and soil. Learning to see it as such invites travelers to experience the Outback not just as observers, but as students of its enduring wisdom.

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, photographed by Nat Hab Expedition Leader © Jamie Smith-Morvell

Reading Rock: Geological Time at Uluru and Kata Tjuta

Nowhere in Australia’s Red Center is time more visible than in the monoliths of Uluru (Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuta (The Olgas). These sandstone giants formed from the sediment of an ancient seabed over 500 million years ago. Their presence today is the result of tectonic uplift, erosion, and an unimaginably long natural history.

The distinctive red hue of the land comes from iron oxide, a natural rusting process that also reveals insights into the mineral composition and chemical weathering of these formations. Some of these rocks are remnants of a once-mighty mountain range—perhaps taller than the Himalayas —now worn down over eons to rolling domes and towering cliffs.

Although central Australia is arid, ephemeral rivers and flash floods have long shaped its topography, carving gorges like Kings Canyon and watering oases like the Garden of Eden waterhole. In geological terms, Australia’s interior provides a rare chance to walk through deep time, to explore an archive recorded on cliff faces and canyon walls.

Kings Canyon

Water Works: Hidden Legacy of Flood, Farming and Fishing

Rock formations and deep canyons are not the only markers of water on the landscape.

One lesser-known fact about water use and management across Australia: the First Peoples were not only hunter-gatherers. Even today, many narratives claim that Europeans introduced landscape-scale agriculture across Australia. Those claims are untrue.

Aboriginal Australians used fire and water manipulation to maintain fertile soil and cultivate native grains, like yam daisies, millet, and bush onions. Evidence of sophisticated, landscape-scale food production includes:

—seed harvesting

—seed and food storage

—intentional reseeding

—soil tilling with digging sticks

Agricultural systems supported semi-permanent settlements, food surplus storage, and social complexity — a clear departure from the outdated hunter-gatherer label.

Red Mullet Fish at the Ubirr Rock Art Site in Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory. Photographed by Nat Hab Expedition Leader © Matt Meyer

At Budj Bim in Victoria, the Gunditjmara people built one of the world’s oldest known aquaculture systems, dating back 6,600 to 8,000 years. An extensive network of channels, weirs, and dams formed with basalt stones traps and houses eels year-round. Budj Bim is a UNESCO World Heritage site, affirming its global importance and engineering sophistication.

Farmed crops and relatively complex management supported predictable seasonal harvests and sustained dense population centers before colonization disrupted these systems.

When European settlers arrived, they did not understand how to read Australia’s vast, arid landscape. They introduced livestock grazing, bore drilling, and irrigation schemes that often ignored ecological limits. This led to overgrazing, aquifer depletion, and the collapse of Indigenous water systems—misinterpreted, in many cases, as signs of underuse or absence.

Today, feral animals—especially camels and cattle—damage fragile waterholes and wetlands, while degraded soils erode more rapidly during flood events. All is not lost. Projects supported by WWF-Australia and Aboriginal ranger groups are working to restore native grasses, remove invasive species, and revive traditional water management techniques.

Witnessing and learning to read floodplains and farmed landscapes as cultural artefacts invites deeper, more respectful travel. The Outback’s stony dry riverbeds carry the imprint of ancient water works—if you know how to decipher them.

Nature’s Window rock formation in Kalbarri National Park, Western Australia.

How Fire Shapes Australia’s Red Center

In this arid land, fire was not always only a threat to be suppressed; it has also been a tool of regeneration and balance. Many native plants in central Australia, like spinifex grass and eucalyptus, are fire-adapted. Some even require heat to germinate.

Fire clears undergrowth, recycles nutrients, and creates patchy habitats that support a diversity of species.

For at least 50,000 years, Aboriginal Australians have practiced cultural burning or firestick farming. Low-intensity, carefully timed burns were used to:

—Manage vegetation

—Reduce fuel loads and wildfire risk

—Stimulate new plant growth

—Creates varied-age vegetation patches

—Supports a diversity of plant and animal species

—Support hunting and ecosystem health

The result was a landscape of mosaic fire patterns, each patch at a different stage of growth and regrowth, supporting a wide range of life.

Modern fire scientists now recognize the brilliance of this Indigenous system. Programs like the North Australian Fire Management Agreement have begun to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into national fire strategies. Controlled burns reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires and help maintain biodiversity in Australia’s Red Center.

On the ground, travelers can see the contrast: scorched earth beside areas of verdant regrowth. This is not random; it’s evidence of fire’s ancient, ongoing role as an ecological tool.

Walking with Culture: Indigenous Practices and Ecological Wisdom

In the Red Center, stories of the land are not metaphors—they are instructions, encoded in song, ceremony and kinship systems. At Uluru and Kata Tjuta, Tjukurpa guides not only the rhythms of daily life, but the laws of the land itself.

El Questro National Park, Western Australia.

Indigenous land custodianship is rooted in care, reciprocity, and responsibility, not ownership. To be from a place is to care for it, listen to it and pass on its stories. Songlines, or dreaming tracks, crisscross Australia in narrative pathways that encode everything from resource locations to migration routes and cosmological events.

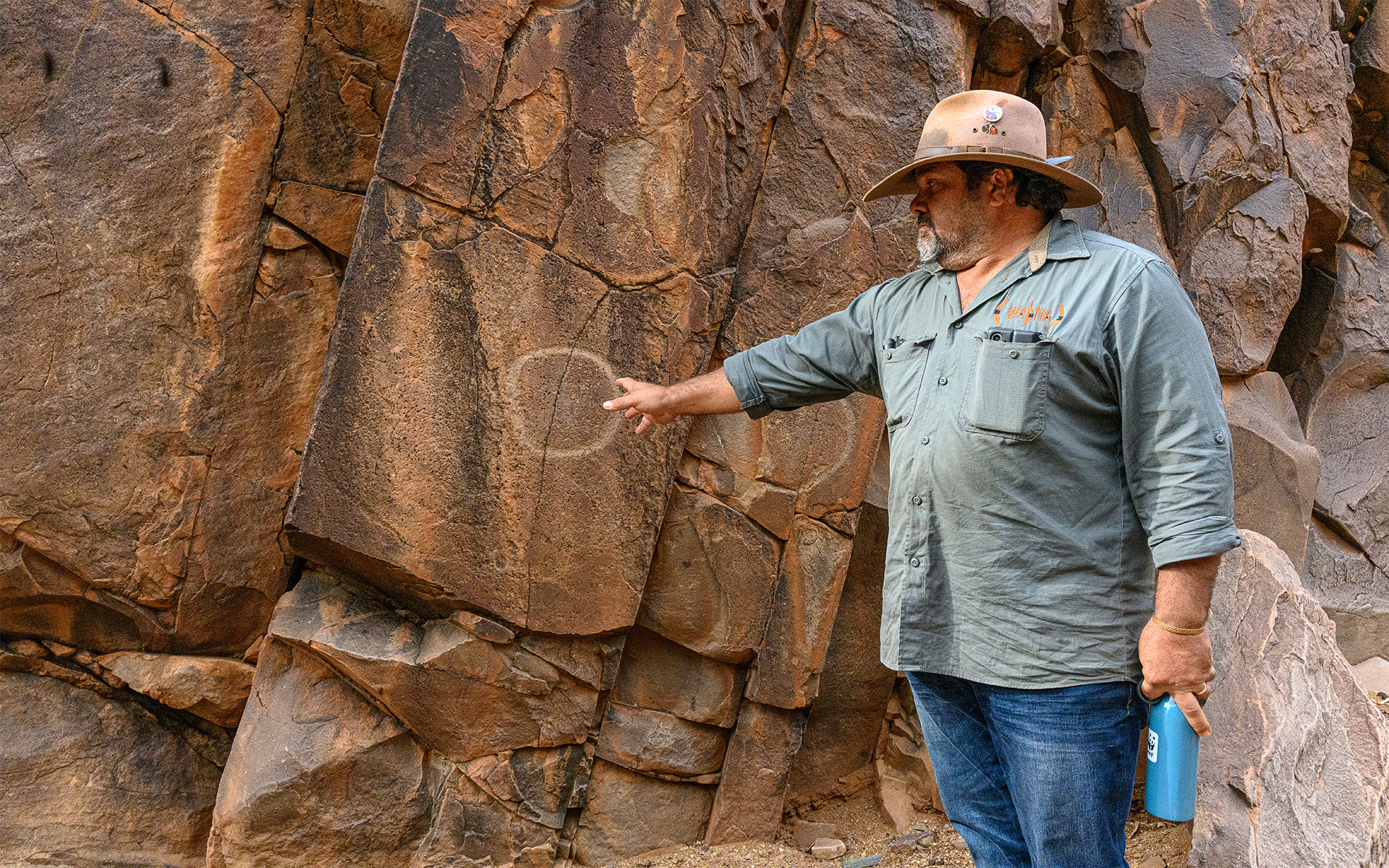

The heart of Australia, shaped by fire and flood over time, reveals memory, knowledge, and care. Travelers on Nat Hab’s Australia North adventure through Uluru and Kata Tjuta can walk with Indigenous guides to learn more.

Ancient Aboriginal rock paintings located at Walga Rock in Western Australia. Photographed by Nat Hab Expedition Leader © Jamie Smith-Morvell

These experiences can shift the way you see—and read—the land. It’s a shift you can carry home. Indigenous ecological knowledge is now recognized by scientists and policymakers worldwide as essential to addressing modern environmental challenges from biodiversity loss to climate resilience.

Join Natural Habitat Adventures in Australia to walk with Traditional Owners, explore sacred sites and experience the Outback as a living archive. Every step is a chance to read a deeper story.

Indigenous guide, photographed by Nat Hab Guest © Patricia Carney